BIG DISCLAIMER: I have never collected a dwarf army. This blog post will be filled with a lot of opinions about dwarves that many Dwarf players will find controversial. Continue reading at your own risk. You have been warned.

When I first got into warhammer I was drawn to Night Goblins. My first minis were the late 5th/ 6th edition multipart plastic night goblins. I remember reading the 6th edition Orc and Goblin book. I loved hearing about the mischievous goblins and their wars with the Dwarves. Out of happenstance I got a copy of 6th edition Dwarves (the blue one.) Over the years I have read that book many times and glanced at it's artwork for untold hours as a kid. Perhaps it is my nostalgia, but GW's Dwarves peaked in this book and it wasn't a high peak.

My goal in this post is to turn my attention toward Dwarves. I am looking to sculpt my own dwarves and this means that I need to reflect on what has come before me, meditate on the essence of dwarvishness. So, here, I will discuss what I see as the trundling and stumbling history of GW's dwarfs - what they sometimes got right, missed opportunities, and where I think they often failed.

The stumbling of the Dwarves

The early history of GW's Dwarves was particularly awkward. Before Warhammer Fantasy 6th ed, Dwarves had no consistent aesthetic in Warhammer. They were a mix of renaissance, norse, and feudal miniatures that never quite fit together.

|

This one ad shows all of the conflicting aesthetics.

|

I think a lot of this confusion stems from a fundamental failure to adopt a unified understanding of what dwarves are. Dwarves, in the larger picture of the fantasy genre, are asked to be two contradictory things. On the one hand they are old, ancient, proud, stubborn craftsmen who live in the mountains, they are a dying race, a marker of older, simpler ways. On the other, people want to characterize them as technologically advanced, a foot-in-the-door for cogs, steam, blackpowder, and machines in a fantasy world of swords. These two interpretations are mutually exclusive and no IP (that I am aware of), in my opinion, has ever pulled it off in a way that feels compelling and consistent. The industrial/societal implications of heavy industry and mechanization are in stark contrast to a society that exalts individual craftsmanship especially the creation of prized weapons like swords, axes and hammers. You have to choose.

Early Warhammer 6th edition married this odd couple the best. The dwarves of the 6th edition blue book presented the most consistent and plausible material culture of this split personality. This edition gave hobbyists an extensive line of miniatures beautifully sculpted by Colin Dixon. The models had a consistent blend of metal, flesh, cloth, and wood textures. The language of the items carried similar motifs - celtic/saxon/viking swirls, iconography, with consistent dwarf interpretations. The warmachines were largely wooden constructs with metal components. [the flame cannon was an exception that broke this aesthetic language.] The clothing styles were consistent. The weapons were largely consistent.

With the release of the later 6th ed. book (the red book) the Warhammer Dwarves had moved on aesthetically. The sculpts of Colin Dixon faded out. They were replaced by more metal textures, more gears, more guns - some of the artillery even featured ammunition akin to what wouldn't appear in real life until the mid 1800s. The peak of the dwarves was brief.

The forgotten height of the dwarves

Once, and only once, GW chose not to force dwarves to straddle the identities of tinkers and smiths. (Well... they did also have those steam punk bathysphere dwarves, but that was after warhammer fantasy ended so it might as well not even exist.) This was in 1988. Soon after the publication of Warhammer 3rd edition. In White Dwarf they published an army list simply titled "NORSE".

In this list Norsemen and Norse dwarves are included side-by-side in a single army list. The men seem to borrow from mytho-history with a combination of huscarls, bondsmen, thralls, and ulfwerenar. The Dwarf contingent of the list is simple. It has berserkers, slayers, and two options of basic dwarf infantry. The army is remarkable for it's complete lack of blackpowder, gryocopters, and artillery and paltry amounts of ranged weapons.

This is an army list that Alrik Ranulfsson would be proud of. This army lacks the pretention and split-mindedness of other dwarf lists. But, it has a problem - the list is basically unplayable in any edition's meta. Dwarves are slow. Depriving them of warmachines, gyrocopters, and blackpowder basically guarantees their defeat as the enemy can largely avoid combat with slow dwarves. So what's to be done? (I propose an answer later, tell me in the comments what you think)

I also enjoy this list because it taps into what I think is the essence of dwarves.

What is the essence of dwarves?

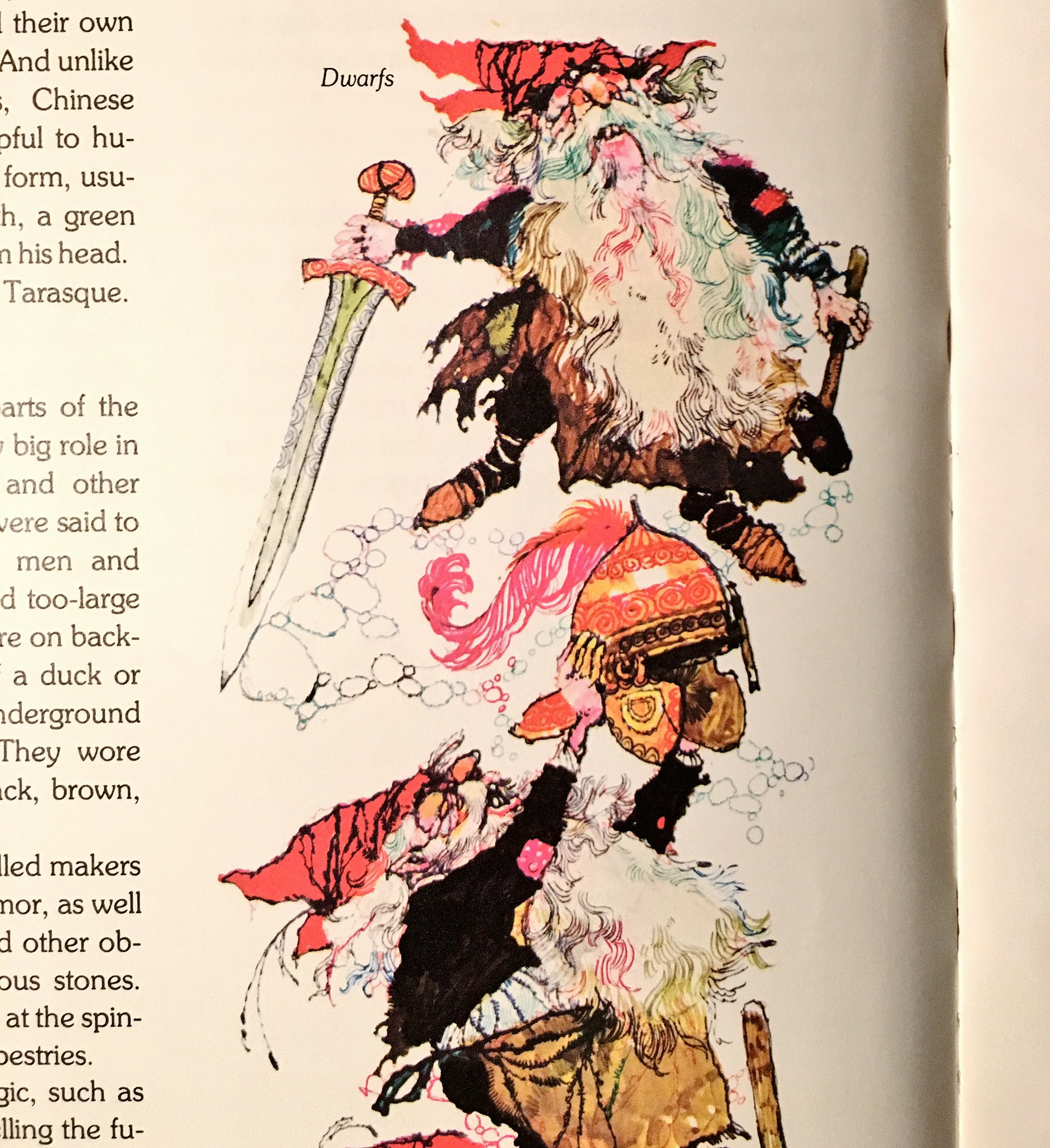

For me, the archetypal seed of Dwarvishness was planted in my childhood mind by Tom McGowen and Victor Ambrus in their 1981 Encyclopedia of Legendary Creatures.

While I can't find the exact text of the passage - what stood out in my child's mind was that Dwarves were ancient mountain-dwelling craftsmen. This view was reinforced when I watched the 1977 Hobbit cartoon.

There's no blackpowder, cogs, cannons, steampower or any of that nonsense here. This depiction of dwarves feels the most grounded to me.

What's your big problem with steampunk anyways?

To be clear, I think steampunk has its time and place. That place just isn't medievalist fantasy settings.

The big issue is that I don't think folks who incorporate steampunk into their fantasy worlds fully consider the social implications of that material culture. (To see a related conversation on material culture read

this.) Briefly, material culture is the physical manifestation of culture - quite literally the material objects made by people of a given culture. Material cultures also refers to common identifying motifs, patterns that arise in a given culture - for example, the bell beaker material culture has similar "bell beaker" pottery found at sites over a large geographic area, so archeologists conclude that these sites must be connected either by trade, shared culture, or other means.

Now, material culture can also tell us other things about communities. If we find large metal objects - like a train, or a cast iron bridge, the existence of these objects implies the existence of the means to produce those objects - massive blast furnaces, vast mines to get the ore and coal, the mass mobilization of laborers for these purposes etc. It is similar to the existence of the pyramids - the pyramids were constructed by people, and their existence and scale presupposes a highly motivated population (at least motivated enough to stack huge blocks to make the things) with exceptional organizational know-how. These corollaries to the material record dispel any notion that ancient people were inherently unorganized, or incapable.

So when we look at dwarves, the existence of something like a flame cannon with a solid metal chassis comments on dwarf social organization and make up. It tells us that vast foundries exist, advanced metallurgical knowledge exists, that some understanding of pneumatics exists, as well as an organized labor force to mine the ores, and fuels. A flame cannon is not the invention of a single individual craftsman, but the shared labor of a team. In our timeline, such a device would not be possible until well into the 1800's.

The other aspect that we need to mention is how human societies dealt with the transition from indivual skilled craftsmen or artisans to the industrial scale of production necessary for large blackpowder armies, steampowdered vehicles, and large iron constructs. When objects are produced by artisans, each object is unique. People know it by who made and who owns it. The object takes on a story of its own. We see this with the way that objects like weapons are discussed in ancient myths. Objects made in this way are inalienable in a sense, that they are grounded in our understanding of place, people, they are part of our story of the world. This is a traditional element of dwarven lore, that they focus on the fine crafting of objects that become key objects in history - like the Hammer of Sigmar, the swords Sting, Glamdring, and Orchrist, or Thor's hammer, Mjölnir.

Industrial production shatters this connection. With the ability to produce a flame cannon, comes the tools to mass produce. Further, the necessity of a vast team of laborers makes the touch of the craftsman disappear. Objects produced in this manner have no personality. In our world, the introduction of mass production stripped proud crafts people of their identity. There were frequent and violent revolts against this process during the early decades of industrialization. This social upheaval was so large that in the 1680s to 1720s it was, in part, responsible for a massive crime wave in London that lead to the creation of modern policing. Manufactured goods were so easily stolen because they were, effectively, identical. People didn't have the traditional connection/identification with their objects so it was easy to steal an object and sell it without getting caught. We must imagine that dwarves would react much stronger to the anonymity of industrialization - it would be completely incompatible with their way of life let alone their individual pride.

A missed opportunity

If we set aside all of this stuff about industrialization and smithing for a moment, there is another element of the GW Dwarves that is both central to their identity but I think also a missed opportunity: words. Words, storytelling, and narrative are big for the dwarves. Runes are the written word. Their weapons literally have written words that effect the world around them. The book of grudges is their written story of themselves. Slayers swear oaths. Oath stones bind dwarves to not yield ground. Old Grumblers are always storytelling about how things were in their day. The 6th edition rulebook is written as if an old dwarf were telling us a story. The 4th/5th, 6th, and late 6th edition books all contain descriptions of how to transliterate the dwarf language. Even the dwarves "hate greenskins" rule speaks to their history.

So as I start thinking about sculpting my own line of dwarves, I have to consider both the constraints of wargaming but also lore and what I want my dwarves to be like. How might dwarves overcome the traditional shortcomings of being slow without recourse to steam, blackpowder, warmachines, or hokey/cringey cavalry options? I think there are two answers to this.

- We can look to the troop options typically available in Saxon and Viking armies - these additions might look like:

- skirmishers with javelins or bows

- hunting dogs

- more maneuverable infantry elements like sea raiders

- We can lean into mytho-history of northwestern europe, we can imagine dwarves with the power of words - runes, spoken stories, oaths, commands, bonds that empower them in battle or harm their enemies - these might look like:

- bards/skalds - story tellers that encourage their allies, or use words to taunt their enemies to charge them

- Runic craftsmen - carving runes in waystones and rocks

- blacksmiths - putting performative words onto weapons

- priests who use words - like a kind of word magic that binds you or the enemy to act certain ways, or speaks things into existence like lightening or fear

- or maybe a caravan/camp with treasure, the implication being the enemy has to come and take the treasure or it's allure causes them to lose discipline and try to take it.

What my Dwarf Range might look like

- Characters

- skald/bards

- warrior-type heroes

- craftsmen chiseling runes on stones

- Infantry types

- dwarves with spears in a shieldwall

- dwarves with swords/axes/hammers in a shield wall

- Dwarves with dane-axes

- Elite Warriors

- Berserkers

- Valkyries/shieldmaidens

- peasant dwarves with javelins or bows

- sappers/mine workers - armed with mail and mattocks

- foresters

- sea raiders

- Others

- battlefield forge

- baggage train with golden hoard

- villagers?

- animal handlers with dogs?

I love your interpretation of dwarfs and how they belong to a realistic world, but does the final product (army) look a lot like your actual gnomes?

ReplyDeleteThen I saw, that you already sculpted humans and gnomes. Will your world add armies like elfs, trolls, faeries, etc?

Thanks for commenting. I am not sure what I will be sculpting after dwarves. The big question for me is what miniatures I want in my collection and whether I think I bring something to the table that other skilled sculptors out there are missing. I haven't started the dwarves yet as I am still wrapping up the humans, but I am optimistic about the project.

DeleteIf you've seen my other work I am very much open to suggestions for other minis to sculpt. Usually a kernel of an idea will get me hyperfixated for weeks.